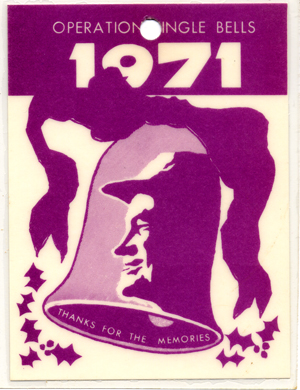

Thanks, Bob Hope, For Remembering

(The Column I Almost Didn't Write)

Thanks For The Memories - too easy a headline to mark the passing of Bob Hope. I wrote it this way: "Thanks, Bob Hope, For Remembering."

Five words above a piece written by a lazy editorial writer who stitched a dozen words onto the top of an Associated Press article. To my amazement, those were the only words I wrote.

I had started down that trail of memories many times over the years, trying to put into words how much the man had meant to a lonely Kansas draftee - more than 31 years ago in Vietnam.

After all, Bob was only 100. Surely he would live forever. I should have known better; I felt the same way about my father.

Christmas 1971 was a lonely time - for me, for all of us, soldiers on the ass-end of a war that nobody back home had the stomach for anymore.

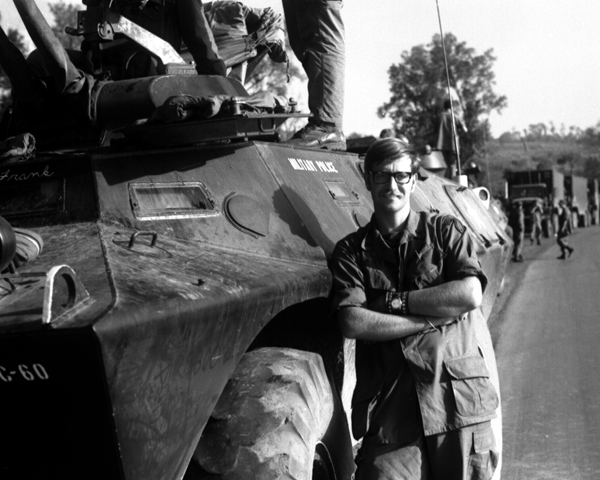

The night before the show, I spent the night stranded on Nui Chau Chan, a mountaintop outpost above a firebase north of Long Binh. That night, I sat amid the sandbags atop a bunker at the edge of the wire, staring blankly into the blackness that sloped off over the trees to the plain below and the vast dimly lit circle that was the Long Binh perimeter.

The flares started popping around midnight - green, red and white - a Christmas present for all of us.

I hadn't planned to be there at all. The assignment was a throw-down story, one I planned to finish by early afternoon Christmas Eve. I was writing about how guys in scattered outposts get paid - and the payroll officer I interviewed said, "Hop in. I'll show you."

I had nowhere else to go, so I jumped in - only to end up hours later at a firebase far away up Highway 1 to the north. The road was posted for travel by convoys only, not single jeeps. The driver had an M16. I had my .45 and a camera.

The two lieutenants in the back had a bundle of cash and a wish to get out and back that day. No time to wait for a convoy.We held our breath, and made it.

At the firebase, we hopped a Huey for a quick lift to the top of Nui Chau Chan, which towered above the base.

The chopper dropped us off and disappeared. Last flight of the day, we learned.

This turn of events upset the lieutenants, who immediately retired to a meal and a bunk arranged by another officer. The driver and I made our way to the small mess hall for something to eat, then fended for ourselves. We decided to hang out with the perimeter guards.

They were good guys - maybe a little crazy, but good guys. I didn't feel unsafe, but I didn't really believe they planned to stay awake all night either.

After the Christmas light show, we listened awhile to the sounds in the blackness - a laugh here, a murmer there, a curse on the far side of the mountaintop. The distant thump of artillery, and the wild sounds of insects in the jungle put us to sleep, somehow comfortable atop a pile of sandbags.

We returned to Long Binh the next morning - the way we had come in reverse order. This time, we were warned not to travel alone. Made no difference to the officers. So we highballed back down the narrow road that should have been safe but wasn't.

I made it back to the Information Office in time for my next assignment - to cover Bob Hope's Christmas show at Long Binh.

I was a journalist for the Army, working at the USARV IO. I had been scheduled to travel throughout Vietnam with Bob Hope's troupe, but my opportunity was squelched by a sergeant who outranked me. He wanted the duty but never wrote a word that I recall.

By my third month in-country, I was somewhat cynical, a bit jaded, a lot homesick. I didn't think I would laugh at many of the jokes.

But you know, when Bob comes out to put on his show, somehow politics doesn't matter any more.

The show was a mixed bag meant to appeal to everyone - baseball great Vida Blue, the Hollywood Deb Stars bouncing and jiggling to Les Brown's "Band of Renown," and Jim "Gomer Pyle" Nabors joking, singing and talking to us like he was an old friend from home.

Bob arrived wearing jungle fatigues covered with unit patches and carrying his ever-present golf club. Although it was 1971 and soldiers fighting the tail-end of this war could have proved to be a tougher crowd than earlier groups, he showed no concern. We were no different in his mind than our fathers in France and our uncles on New Guinea.

And, he was smart enough to know the crowd would appreciate the girl on his arm - Brucene Smith, Miss World-USA, whose Texas good looks were a stark contrast to the dust-covered green of the Army post.

It was somewhat magical how this man somehow knew the secret; how to put smiles on faces that had been blank just moments before, how to restore the twinkle to eyes that had been so cold.

His well-worn routine brought laughs and groans, but we knew the cornball gags were pulled from a vast collection of jokes, skits and one-liners perfected over many years in a hundred places soldiers, sailors, flyers and marines gather away from home.

We knew many of those one-liners had been tested on our fathers in earlier times, and that connected all of us.

As we neared the end of 1971, we knew our unpopular war was winding down, that we would not be going home as heroes.

But on that day, at that moment, in a Long Binh amphitheater carved out of the earth by bulldozers, we were the center of the universe - because a 68-year-old comedian with a special feeling in his heart for soldiers cared enough to give up his holiday for us.

Thanks, Bob Hope, for remembering.

Written by Dave Berry, copyright Tyler Morning Telegraph, Memorial Day, 2004. Bob Hope died at the age of 100 on July 29, 2003.

< Back to Vietnam Gallery