The Empty Grave in Mrs. Lee's Garden

By DAVE BERRY

There's an empty grave at the edge of Mrs. Lee's rose garden. No monument marks the spot. The original occupant of that space in the flower-lined row of gravesites departed long ago to a quiet location far away ... his story still not written.

The fourth murderous summer of the Civil War was nearly spent. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant had thrown his once-mighty Army of the Potomac against Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia in a series of man-wasting battles. They clashed in the Wilderness, at Spotsylvania Court House and at Cold Harbor, a crushing defeat for the Union. The Battle of the Crater and clashes around the fortifications of Petersburg and Richmond had only added to the carnage.

A bloody stream of wounded flowed toward Washington's 36 overstretched military hospitals. And the cemeteries were full.

Lincoln's Quartermaster Gen. Montgomery Meigs, tasked with finding a suitable spot for a national cemetery, had but to look across the Potomac. There, on a wooded Virginia hilltop overlooking the capital, sat a beautiful mansion. Abandoned by its owner, the estate had been purchased at auction by the federal government. Meigs ordered future burials begin "immediately around the house of General Lee, on Arlington Heights, for the burial of soldiers dying in the army hospitals of this city."

When Union officers quartered in the Confederate general's former home resisted efforts to locate graves near their billets, Meigs persisted. That was his intention, he said, to render the property uninhabitable should the Lee's envision returning.

Each Memorial Day, when flags sprout over the graves at Arlington National Cemetery, there's a gap in the row of banners along the east edge of the rose garden. One grave Meigs ordered placed at the garden as a political statement is gone, it's occupant exhumed. It remains unfilled to this day. I believe I know its former occupant.

Hartman Sharp Felt lived a full life in his 28 years. He had taken part in the nation's westward expansion and joined the rush to the California gold fields. He saw the rendering of the union and led men in battle to preserve it.

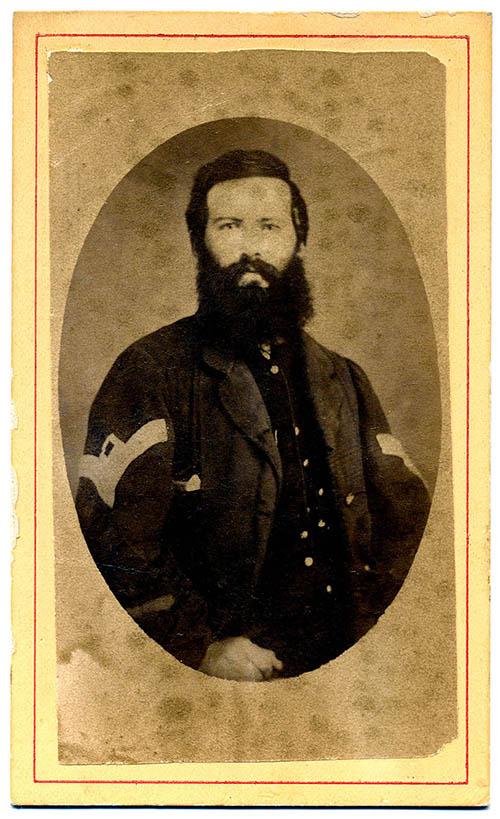

Hartman - or Harty as he liked to be called - is my wife's great-uncle, the oldest brother of her great-grandfather. When I first met Harty, his story was untold. He was the unidentified soldier on a small carte-de-visite in a leather-bound photo album my mother-in-law kept. His friendly face was framed by a full beard and dark hair accented by a white patch on his left temple. He was a big man and sported the stripes of a first sergeant. A Felt family historian gives him only a scant mention.

I knew there was more to his story. And I set out to tell it.

Research can take you on a remarkable journey. My trail led through a dozen libraries, into the bowels of the National Archives, to the Library of Congress Reading Room and its trove of documents, to the copse of trees at Gettysburg, the sunken road at Antietam and the low stone wall on Marye's Heights at Fredericksburg. It took me into muster rolls, sick call reports, hospital death records, Civil War newspapers, and down a thousand trails online and offline. Not only could I write a book on him, I did.

Harty fought with the 7th Michigan Infantry, a regiment known for its steadiness under fire. A horribly battered regiment in the Army of the Potomac, it weathered the bloody slaughter in the West Wood at Antietam, spearheaded the attack at Fredericksburg by attacking across the Rappahannock in boats and helped beat back Pickett's charge on the third day at Gettysburg.

The regiment took immense casualties. Of more than 2,000 Union regiments, only 32 would suffer more killed and wounded in battle than the Seventh Michigan. Early in the war, Harty was shot in the leg, and a minie ball grazed his temple at Fair Oaks, causing the white patch in his hair. Nursed back to health, he was mistakenly listed as a deserter when he returned to his Company B comrades too early. He rose through the ranks from corporal to sergeant... and then to first sergeant.

After Gettysburg, his enlistment up, Harty could have gone home, leaving the war behind. The Seventh was a shadow of what it had been, barely large enough to sustain it as a regiment. Instead, during the winter of '63, he reenlisted as a veteran volunteer for the "duration of the war."

In the heat of July 1864, under a new blue and gold regimental banner sewn by "the ladies of Monroe," Harty was commissioned a second lieutenant and transferred to Company C, an undersized company with just 35 men. Many were sick or nursing wounds, but they were good men... no bounty men, no draftees, no slackers. All had been tested, even the new recruits - at Cold Harbor and the Wilderness.

On Aug. 14, 1864, the regiment was part of a major flanking maneuver by Grant's Army of the Potomac. Acting under bad information that Lee's defenses around Richmond had been weakened at the breastworks along Deep Bottom Run north of the James River, he targeted his assault there.

Confederate forces had not been weakened. In fact, they had been reinforced. The breastworks stretched along the far slope of a deep ravine, bolstered by two ditches that ran along the bottom. Once across the ravine, attackers would face a steep climb up the slope to the first of three trenches, all of which bristled with rebel bayonets.Harty led his men down into the ravine before he was cut down. The attack stalled, and both sides blazed away until dark, when the union withdrew. As Gen. Meigs looked for additional cemetery space in Washington, Harty's litter bearers sought a place for the mortally wounded lieutenant among the human cargo that covered the deck of the troop transport "State of Maine" on the James River.

As Meigs argued with officers inhabiting Arlington House, the boatload of misery bumped ashore at the Seventh Street Steamboat Landing near Armory Square Hospital (on Independence Avenue where the Air and Space Museum stands today).

Assessing the wounded by torchlight, Chief Surgeon Willard Bliss judged that Harty's arm could be saved, but the bullet lodged near his shoulder blade was poisoning his system and needed to be removed right away. It had been four days since the battle, and he feared it might already be too late.

Harty awoke in Bed 36 of Ward K, one of twelve pavilions at Armory Square Hospital, the largest of Washington's hospitals. Ward K was reserved for the worst cases, those whose chances of survival were slim. But Harty had made it from the battlefield through transport and surgery. Now doctors could only watch and wait.

Among the watchers were Walt Whitman and Louisa May Alcott, who visited Ward K often. Whitman filled notebooks with scribbled notes about those visits. Abraham Lincoln came regularly to Ward K, stopping at each bed. Mrs. Lincoln often slipped in unannounced, delivering a motherly touch and a smile before departing.

Hartman Sharp Felt would not survive. He died Aug. 24, ten days after the battle. A dozen more young soldiers would join Harty on the boat ride to Arlington for burial. Their graves would be placed along the estate perimeter. Harty, as an officer, would be laid to rest near the Lee mansion as Gen. Meigs had commanded.

Harty left no letters and no diary. But his story was all there, a fascinating saga waiting for someone with the desire to follow the clues and piece it together from the archives, libraries, history books, muster rolls and newspaper clips.

When I stood at the edge of Mrs. Lee's garden, smelling the roses and enjoying the quiet of Lee's old home, I realized I was near the end of my search. Comparing death dates on markers to each side, I searched my notes again, made some educated guesses... and felt confident this was Hartman Felt's final resting place, at least for a time, until his father and brothers arrived to take his body to Grass Lake.

I felt I could finally write his story ... what I knew and what I believed. I wanted to believe his spirit roamed free, with friends who had fallen before... those buried in the mud of the Peninsula, in the frozen ground before that horrible wall at Fredericksburg and in the cornfield near the West Wood at Antietam. I felt confident Harty had returned to check the pickets defending the stone wall at Cemetery Ridge, rounded up those left behind in the retreat through Savage's Station and aligned the skirmishers lost in the smoky hell of the Wilderness.

Harty was a good first sergeant to the end, accounting for and seeing to the needs of each man before looking after himself. Today, his duty done, he's at rest in a quiet graveyard in Grass Lake, Mich., far from the politics of Washington, D.C., and the killing fields of Virginia.

Dave Berry is the retired editor of the Tyler Morning Telegraph. This column, published June 1, 2016, was his last for the newspaper but not the last story he hopes to tell.

Photo of Hartman Sharp Felt, First Sergeant, Company C, 7th Michigan Infantry Regiment. (Unknown photographer 1862)