Farewell to the Texas Prison Rodeo

By DAVE BERRY

Brazoria County, along the Texas Gulf Coast, was home to almost as many prisons as chemical plants.

When I lived and worked there in the early '80s, it seemed all roads led past one of those sprawling detention centers... and in lush South Texas, inmates worked the expansive fields around the prisons under the watchful eye of a guard on horseback - usually with a big Stetson and a long shotgun.

At my newspaper, prisons were a news beat, part of normal coverage, a major local industry... and we kept an eye on them.

I well remember a day inside the Darrington Unit, escorted down the long hallways by a stern-faced armed guard, who warned about crossing the yellow lines that ran down each side about two feet out from the cells. That's where the inmates walk, counter-clockwise, no lollygagging, right shoulder nearest the barred doors.

"Stay in the middle," he urged.

We weren't overnight guests, just a couple of visiting journalists, cleared for an interview with the warden. If that went well, we hoped he would grant our request to enter one of the cellblocks to interview movie star George Kennedy, a character actor probably best known for his role as Dragline, Paul Newman's prison farm buddy in Cool Hand Luke.

Kennedy was filming far inside the prison, and we found him trying to get into character, a big man folded uncomfortably into a smallish bunk in a two-man cell. We ducked through the barred door and perched on the bunk across from him. There, sweating, knees almost touching, steel springs of the bunks creaking with every move, the three of us lobbed questions and answers back and forth in that tiny space across the steel toilet that jutted from the wall.

The movie was far from memorable. A 1980 flick called "Hotwire," critics labeled it "the worst of the year" and "so bad, it's fun to watch." It never made it to the little theater in Lake Jackson, the Freeport drive-in or even late-night TV, so I have yet to see it.

That single visit inside the prison and my interview with the warden yielded a story for the next day, but the biggest reward came later... an invitation to the historic Texas Prison Rodeo, just before it officially faded away into history.

The Prison Rodeo, launched in 1931 at the height of the Depression, was first held in the "Walls" unit baseball park in Huntsville. By year two, it drew 15,000 fans.

To capitalize on its success, a special security-minded rodeo arena was built, and soon the event attracted 100,000 over four weekends. The Texas Prison Museum called it "the largest crowd of any sporting event in Texas" at the time.

Held every Sunday in October, it became a Texas tradition.

It was not a gentle show. In addition to saddle bronc riding, bareback bronc riding and bull riding, events also included wild cow milking, calf belling, goat roping, wild mare milking and bull dogging.

The most popular attraction, and probably the most controversial, was the "Hard Money" event. Forty inmates in red shirts rushed into the arena with a wild bull. A Bull Durham sack tied between its horns contained at least $50, but other donations in some years took that up to as much as $1,500. The man who successfully snatched the tobacco sack from the horns of the bull could keep what was inside. While the mad scramble for the money was a crowd pleaser, inmates were gored, thrown through the air and seriously injured in the event. Still, there was no shortage of volunteers wanting to take the risk. Often, the winner enjoyed his treasure only after a visit to the infirmary.

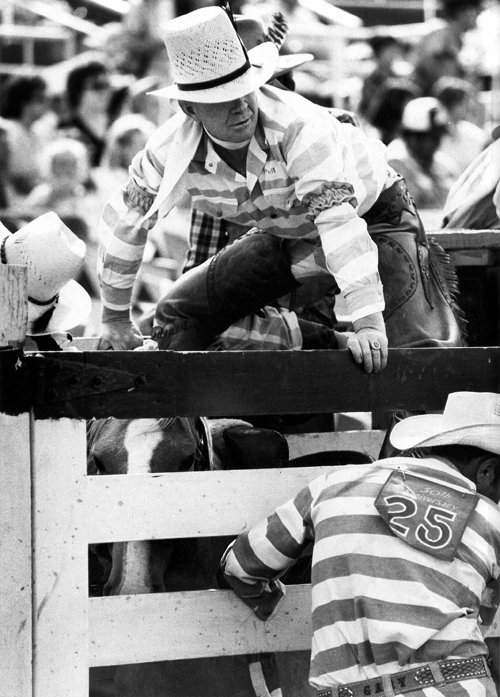

I was fortunate to have attended and photographed one of the last prison rodeos, the 50th Anniversary event in 1981. With the press pass the warden granted, I was free to roam among the inmates, inside the arena at times, hanging on the gates and fences when the action got too intense.

In interviews and photos, I tried to capture the excitement, laughter and danger of that crazy spectacle. Convicts in cheap cowboy hats, beat up boots and striped shirts, sporting exquisite hand-tooled leather belts and chaps, were happy to be free of the daily prison routine, proud to have been chosen to work with the animals, thrilled at the prospect of competing, glad to take part in something special ... feelings they hadn't felt in awhile.

Four years later - for good or for bad - the historic convict performances shut down. Some blamed changing attitudes about treatment of inmates. Others said it had more to do with the deteriorating condition of the arena. Either way, I have to believe the cowboys were disappointed.

That day, I drove away from the guards with shotguns. I was free to go.

I thought, just maybe, the bronc riders had felt a hint of freedom ... if only for a brief moment.

Behind me, the cowboys were herded back inside, exchanging leather chaps, boots and belts for striped uniforms, nursing sprains, breaks and bruises at the infirmary.

Then, single file, they returned to their bunks, staying right of the yellow line, walking counter-clockwise, no lollygagging, right shoulder nearest the barred doors.

Dave Berry is the retired editor of the Tyler Morning Telegraph. This column ran on April 9, 2014.